#17

Blindfolded

What is for you the most precious sense and why?

Violence Closes Distance

Collage based on a photographic archive from the war in Bosnia: an eye reflected in the lens of a sniper.

© Imperial War Museums, London. Photograph taken between 1992–1995.

Dear Sophy,

Without hesitation: the eye. Not only because my artistic practice as a photographer is anchored in the visual, but because I share Shakespeare’s conviction that the eyes are the mirror of the soul. The eye does not merely see; it mediates. It is a border post between interior and exterior, a threshold where the world enters us and we, in turn, expose ourselves to the world.

Eyes betray what language conceals. They open like doors of the soul. When you look at someone you love, you allow love to enter; when you look at the world, you allow it to speak. That this exchange is possible at all remains a miracle. For that very reason, the sudden loss of sight, without time, without mourning, without adaptation, would feel to me like absolute powerlessness. Not merely the disappearance of color, but the interruption of narration itself. As if the world were to lose its grammar overnight.

This is not to say that blindness marks the death of the soul. On the contrary. Monet, as his vision deteriorated, reinvented painting at the precise moment photography was thought to have rendered it obsolete. Milton gave Paradise Lost its moral density only after losing the light. Such transformations are miraculous, but miracles presuppose time: mourning, adaptation, the slow recalibration of perception and selfhood.

What troubles me today is something else entirely. We are witnessing blindness not as fate, but as procedure. Not as tragedy, but as technique. Vision is no longer merely lost; it is taken. The eye has become a geopolitical battleground.

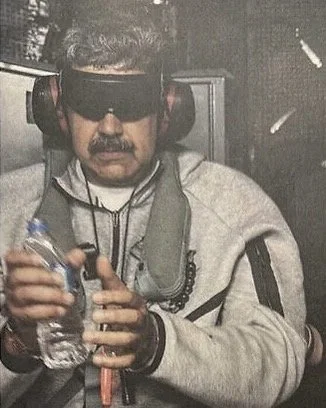

I am thinking of an image currently circulating with the force of a political hand grenade: Maduro, blindfolded. This is not simply a man who may not see, but a body recoded into a sign. Something decisive happens in such images. A person is not only captured; he is fixed, like an insect, within an iconography, archived within a visual regime of crime, discipline, and punishment.

This gesture belongs to a long and chilling visual choreography. It stretches from World War II to the War on Terror, from Afghanistan to Iraq, from occupied Palestine to the present moment. John Walker Lindh, bound and blindfolded after his capture in 2001. German U-boat survivors escorted ashore in 1943, eyes covered, humanity suspended. The hooded Iraqi detainee at Abu Ghraib, standing on a box, wires attached to his body. Blindness staged as total vulnerability. Eden Abergil smiling beside blindfolded Palestinian detainees, folding military domination into the grammar of the selfie.

John Walker Lindh

U.S. citizen bound and blindfolded after his capture by American forces during the war in Afghanistan; later internationally known as the “American Taliban.”

© Wikimedia Commons. Photograph taken in Afghanistan, December 2001.

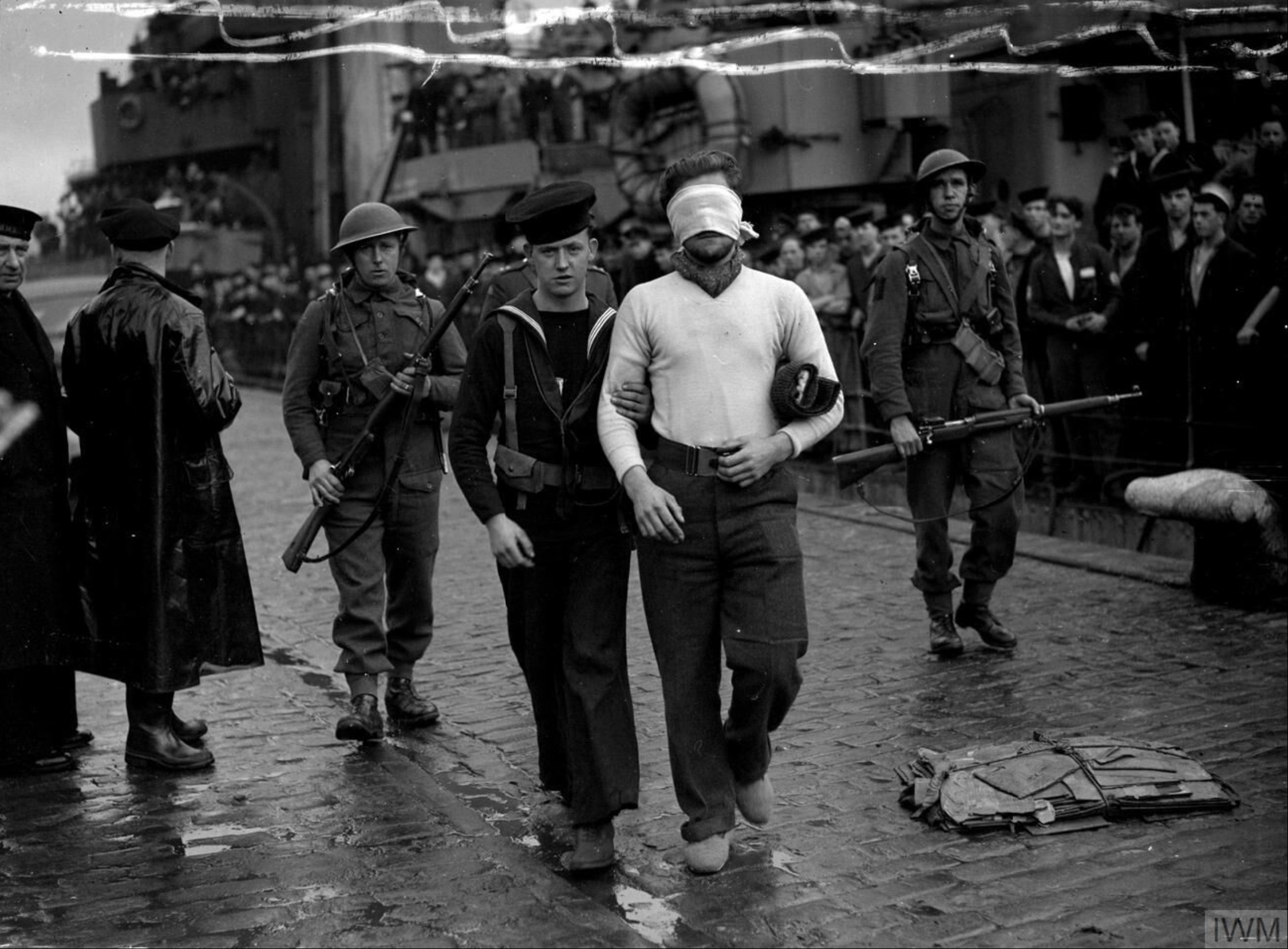

Nazi U-boat Survivors

British sailor escorting a blindfolded German war prisoner after the rescue of U-boat survivors by HMS Oribi and HMS Orwell, following the sinking of the submarines by Coastal Command aircraft.

© Imperial War Museums, London. Photograph taken at Greenock, 11 October 1943.

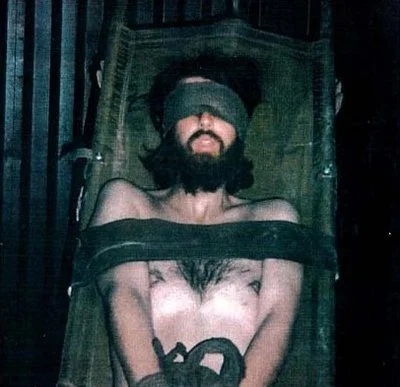

Abu Ghraib Detainee

Hooded Iraqi detainee standing on a box with wires attached to his body inside Abu Ghraib prison; image later released as part of a series documenting the abuse of detainees by U.S. military personnel.

© Wikimedia Commons. Photograph taken in Iraq, 2004.

Eden Abergil and Palestinian Detainees

Israeli soldier posing for the camera beside blindfolded and handcuffed Palestinian detainees; photograph later circulated online after being shared on Facebook, from a Facebook album titled “Military, the most beautiful time of my life.”

© Sachim Blog (Tumblr). Photograph taken in the occupied Palestinian territories, c. 2010.

Across these images, blindness functions not as concealment but as exposure. To be blindfolded is not simply to be deprived of sight; it is to be stripped of recognizability. A face with visible eyes invites identification. A covered face slides toward abstraction, toward the status of a body already halfway to a corpse.

Here, visual culture reveals its most violent capacity. To blind is to dehumanize preemptively. The bullet is postponed; the soul is neutralized first.

Trump understands this instinctively. As a master of spectacle and symbolic aggression, he weaponizes visual culture with ruthless efficiency. To take someone’s eyes, symbolically, photographically, theatrically, is to render them powerless without killing them. It is Shakespearean in its cruelty - no doors left to the soul, no reciprocal gaze, no remaining claim to interiority. A living body reduced to a prop; a person exiled into the underworld of the unseen.

And this is why your question presses so urgently now. What would wound me most is not simply the loss of sight, but its violent confiscation - blindness imposed as domination. In that act, geopolitics and sensory existence intersect at their most brutal point. The eye is not just a sense. It is a claim to mutual recognition. To take it away is to declare: you will no longer appear as human. That, for me, is the deepest violence.

With love,

Coma